Australia’s News Media Bargaining Code: changing dominance structures in tech

The Australian Government passed the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code on February 25, and it now awaits Royal Assent. The Amendment inserts a new Part IVBA into the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 to establish a mandatory code, under which registered Australian news corporations and designated digital platforms will have to comply with certain requirements, including non-differentiation and the provision of information as required. News companies would also be in a position to negotiate the remuneration to make available their news content on these platforms. The rationale for such an addition is to address the bargaining power imbalance between digital platforms and Australian news businesses.

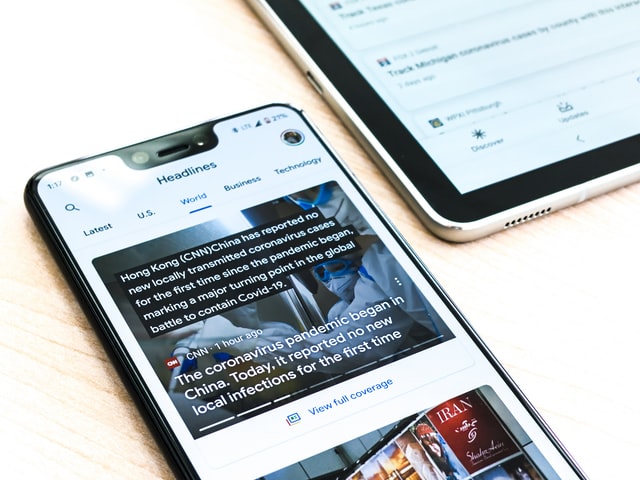

The extent of the power imbalance is evident from the series of events that culminated in the amendments to the proposed law. Google had initially threatened to pull its search functions in the country, but later entered into agreements with a number of news publishers in an effort to get ahead of the law. With a fraction of the market share of Google’s search engine in Australia, Microsoft backed the new code. Facebook, however, blocked Australian news organizations from posting content on its platform. This inadvertently also led to other types of content being blocked, significantly affecting users. While Facebook has now restored the news pages on its platform in Australia, it maintains that it will retain the decision as to whether news will continue to appear on its platform at a later stage in order to avoid being automatically forced into a negotiation.

Countries have been attempting to find a balance between innovation and consumer protection for years, Australia’s new law could likely set a precedent in terms of regulating US tech giants. The incident in Australia has fuelled demands in the US and in other countries for greater regulation of the growing influence of Big Tech. Facebook has, over the years, come under scrutiny over anticompetitive practices and privacy concerns. It is also facing charges under antitrust laws in the US relating to its dominance in the social media sector through its acquisition of Whatsapp and Instagram. Facebook and Google’s dominance in the advertising space has also garnered regulatory attention. By offering many of its services for free, these companies are able to maximize their data collection and advertising capabilities, turning the antitrust doctrine on its head. Amazon’s price wars have garnered considerable criticism, as has its use of the data it collects in its role as a marketplace, to develop copycat products to take over markets.

Tech companies have largely grown by successfully mining data and using it to their advantage. The evolution of idealistic innovation into Machiavellian aggressiveness has resulted in products without safeguards and an overall lack of accountability in technology. In order to curb the unregulated and arguably unethical use of consumer data by companies, many countries are coming up with data protection laws such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, the California Computer Privacy Act, and India’s Personal Data Protection Act, to safeguard the interests of their citizens, and to protect themselves in the event of data breaches. Furthermore, Big Tech companies are being found responsible for the amplification of misinformation and hate speech on the internet through their algorithms. Lawmakers are grappling with the complexity of the issue, and there have been calls to establish regulatory bodies, since the companies have been unable or unwilling to sufficiently self-regulate.

Given how regulation in technology has been limited in recent decades, there have been demands to break up Big Tech in order to level the playing field. While this might not happen in the near future, regulatory reform appears to be on the horizon, as governments are slowly realizing they might be up against Goliath.

The right to repair movement could have a significant impact on global emissions reduction

Many manufacturers use planned obsolescence so that products fail prematurely and are short-lived, t

The integration of healthcare and VR

Virtual reality (VR) has largely been associated with the field of entertainment. However, scientist

The increasing number of internet blackouts worldwide is cause for concern

While internet blackouts first found favor in situations of political unrest, over the years, the pr